CINCINNATI — Who is Cincinnati’s worst landlord? That’s difficult to say. But an argument could be made for Byron Germany.

Byron Germany

He was sentenced to 90 days in the Hamilton County Justice Center because of the way he managed Phil’s Manor, a three-story apartment building he owned in West Price Hill that was condemned as a public nuisance by the city in May and demolished in October.

“There was no water and no plumbing for the tenants,” Hamilton County Municipal Judge Brad Greenberg said. “There were children living there. People had to put their human waste in garbage bags and dump it out the window.”

Because of stories like Germany's, WCPO spent nearly a year exploring crime stats and code violations tied to Cincinnati rental properties. We talked to city officials, neighborhood leaders, tenants, landlords and people who own businesses and homes near problem properties to gauge the impact of blight.

As you’ll see from this WCPO Special Report, the problem is complex and the impact pervasive across the city of Cincinnati.

The challenges range from crumbling houses that cash-strapped families turn to as a home of last resort to massive low-rent apartment communities so neglected they have become hubs for neighborhood crime and decay.

“This is clearly an incredibly important issue facing our most under-resourced communities,” Cincinnati City Solicitor Paula Boggs Muething said.

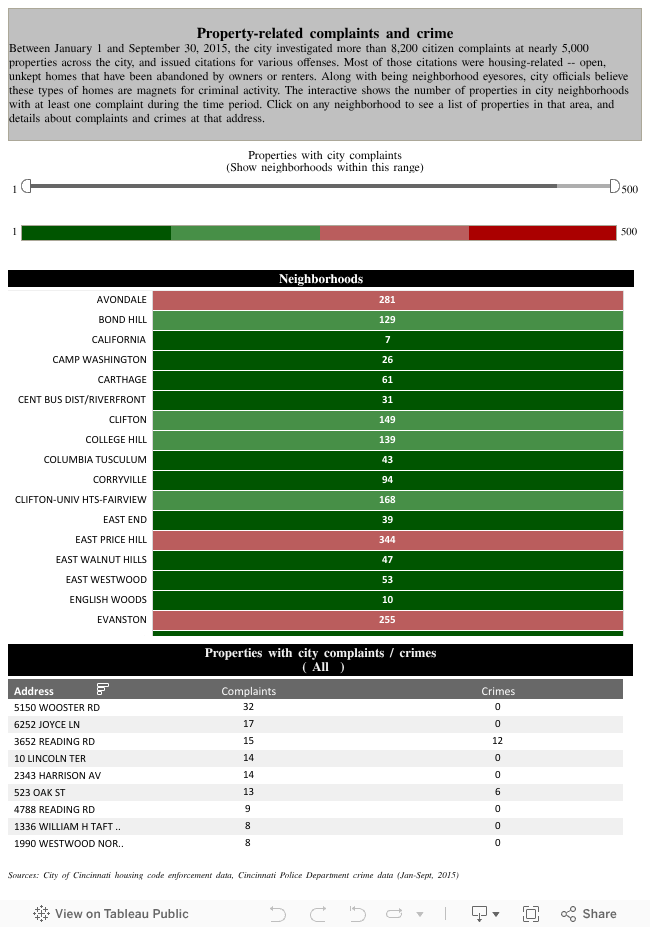

WCPO data show there were 4,740 properties that had at least one building code complaint filed with the city of Cincinnati between Jan. 1 and Sept. 30 of this year. Those properties attracted 6,388 complaints documented by police and city inspectors.

WCPO's analysis found:

• The largest portion of complaints — 2,931 or about 46 percent of the total — were for housing-related problems, such as vacant homes left unattended, no heat or water, broken windows, leaking roofs and the like.

• The next highest portion of complaints — 1,746 or about 27 percent of the total — were for litter-related problems. Also high on the list were problems classified as environmental. Those problems include pests and rodents, bird droppings, dog waste and mold inside or around a property.

• There were 35 properties around the city with five or more complaints since January. The property with the most complaints, a whopping 17, is the administrative address for Roselawn Village apartments. All 17 were housing-related complaints.

• The 4,470 properties seem to be a breeding ground for criminal activity, too. Since January, there have been at least 1,241 major crimes reported at the properties. The includes three homicides, 292 assaults, 45 robberies, eight rapes, 230 burglaries, 213 thefts and seven incidents where a weapon was illegally fired on or around the property.

The interactive graphic below shows how the troubled properties reach beyond just one or two spots in the city.

“Ultimately, these are serious health and safety issues that we’re seeking to have corrected for the benefit of the residents and the surrounding community,” Boggs Muething said. “The effects of it kind of bleed into the neighborhood. It’s important to address it and make changes at that problem property in order for the rest of the neighborhood to begin to recover from the damage it’s caused.”

No Money, More Problems

Part of the blame for Cincinnati’s problem property plight can be pinned on the economy, and perhaps, investor impulses.

Leading up to the recession, a speculative decade of property flipping, loan defaults and declining occupancy caused many landlords to defer maintenance — or avoid it altogether.

“Generally speaking there was more distress in older properties. They cost more to operate,” said Dave Lockard, senior vice president for CBRE, a commercial real estate firm that regularly surveys the owners of 60,000 Cincinnati-area apartment units.

In the last five years, CBRE documented a 20 percent increase in average Cincinnati apartment rents to $837 per month. But it was an uneven recovery, with high-end apartments posting bigger rent gains than those catering to low-income renters.

This year, Lockard said “Class A” properties, including newer buildings at The Banks, Downtown and Oakley, are seeing rent hikes of 4 percent, double that of affordable units.

But low-income renters are struggling to keep pace with any increase, according to a study published in September by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

The study found 11.8 million renters in the U.S. are “cost burdened,” which means they spent more than 50 percent of household income on housing expenses. That number is predicted to rise by 2025 to 13.1 million households, an increase of 11 percent, driven by rising rents and sluggish income growth.

In Cincinnati, the percentage of cost-burdened renters is 30.5 percent. That’s higher than Columbus, but lower than Cleveland, Akron, Dayton and Toledo.

The end result is a segment of the housing market in which landlords and tenants alike are struggling to make ends meet more than six years after the end of the Great Recession.

“I’d leave, but everything else is too expensive,” said Charles Williams, who pays $25 a month for his one bedroom apartment in Avondale. The federal government picks up the remaining $500 charged by his landlords, New Jersey-based PF Holdings.

In spite of PF Holdings receiving nearly more than $560,000 a year in taxpayer money for the nearly 100-unit property, the building has made Cincinnati’s chronic nuisance list for a host of health and safety code violations.

The city passed a chronic nuisance ordinance in 2006 (and revised it in 2010) that allows city officials to track properties based on police runs, crimes and code violations. Properties that rank near the top of these lists are targeted for additional enforcement.

Charles Williams

“This is an old building,” Williams said. “But the owners, they’ve got new money. You can just look around and tell they’re not spending any of it here.”

Fighting the Uphill Battle

Several city departments are trying to combat the problem, including the law department, police, building and health inspectors.

Six members of Cincinnati City Council have signed an ordinance in support of establishing a housing court that would beef up the city’s enforcement powers against problem-property owners. City Manager Harry Black has his data guru working on a “next-generation breakthrough” that uses existing city data to predict which properties should be targeted for enforcement to prevent blight.

But none of these approaches has been able to shift the city’s enforcement efforts from a complaint-driven system that reacts to problems instead of preventing them.

“Every lead case I have on my docket comes from a discovered lead poisoning of a child,” Judge Greenberg said. “That’s how they come to the attention of the city. A child shows up exhibiting symptoms of lead poisoning and that sets off an investigation.”

The Ohio Department of Health calls lead poisoning "the greatest environmental threat" to Ohio's children because of an estimated 3.7 million housing units statewide that contain lead-based paint. Lead can damage every system in the human body, but children under 36 months are particularly susceptible to permanent brain damage from even small exposures. Ohio tested 153,010 children for lead exposure in 2014 and found 1,298, or 0.89 percent, with elevated blood levels of lead. In Hamilton County, 0.73 percent of the 15,935 children tested had elevated lead levels.

And that's just one of the myriad problems that come with sub-standard housing. Few of the problems can be tackled quickly, putting a strain on city resources as lengthy legal battles ensue.

One such battle is scheduled for trial Dec. 16. The city has accused PF Holdings, the Jersey-based owner of six apartment communities that are home to nearly 800 local residents, of letting its properties become a public nuisance. City attorneys are asking that a receiver be named to manage rents and the properties. The case has taken nearly two years to come to court.

PF Holdings attorney Steven Rothstein contends the owners have invested "hundreds of thousands of dollars" to repair a host of issues they inherited when they purchased the properties in 2013.

"Every spare dollar that the ownership has over and above the mortgage, taxes and insurance is being devoted to maintenance," said Rothstein. "They have no interest in litigation. They are interested in fixing the problems."

Meanwhile, West Price Hill landlord Byron Germany on Sept. 1 became just the second person this year to be sent to jail on building code violations by Judge Greenberg. Germany was charged with failure to comply with the lawful order of the department of building and inspections. Germany, through an attorney, declined comment for this story. Two of his tenants submitted affidavits seeking leniency for their landlord.

Germany's sentence was "way too harsh for a man who defiantly took care of us," wrote Sonya Frazier. "He ensured I had 50 gallons of water a day."

The judge said city attorneys and inspectors told him that Germany “fled from police” when they tried to address his property as a neighborhood nuisance. It was a two-year process that eventually brought a demolition contractor to 4373 W. Eighth St. Germany spent more than two months in jail before Greenberg allowed him to be part of the county's work-release program on Nov. 19.

City attorney Mark Manning described Germany as "a drug-dealing, violent criminal" who told Greater Cincinnati Water Works the building was vacant but continued to rent to tenants who were afraid to cooperate with building inspectors and police. Germany pleaded guilty to cocaine possession and drug paraphernalia charges in 2013 and was charged with aggravated menacing in 2014, though that charge was dismissed in January, according to court documents.

When city officials stepped up enforcement, Manning said Germany started flipping the property to various family members and a phony charity to escape enforcement.

“Probably the worst case I’ve had this year,” said Greenberg, who runs the weekly housing docket for Cincinnati code-violation cases that result in criminal charges.

“It’s important that landlords realize that they’re not under an obligation to provide the Taj Mahal,” said the judge. “But they have to provide a safe, healthy environment for tenants. That’s their legal and moral obligation.”

Meanwhile, neighborhood advocates watch as the problems spread.

"Blighted properties affect every neighborhood," said Ken Smith, executive director of the community improvement group Price Hill Will.

Unless addressed and prevented, advocates warn the impact could be dire — threatening to take out entire city blocks and communities.

"It's like a cancer metastasizing," Smith said.

Keep reading for stories about the people whose lives are being impacted by problem properties throughout the city:

- Landlord gets millions while properties, tenants suffer

- Winning an eviction hearing is no victory for this family with no place to go

- A $50 million plan can't come fast enough for residents of Avondale apartments

- Blind grandmother goes from bad to worse – a rental home with no running water

- Small business owner battles 'nest for prostitutes' in Price Hill

- Retaining wall leads to long-running legal battle for East Price Hill homeowners

- Solutions, resources scarce for Cincinnati's most troubled properties