CINCINNATI -- Federal agents tasked with getting illegal guns off the street traced nearly 1,500 firearms confiscated by Cincinnati police officers in 18 months, a WCPO analysis found.

But even with a paper record that reveals who originally purchased each firearm and where they bought it, officials don't often have a definitive answer on how a gun used in a crime got into the wrong hands.

"Firearms have a long life. It's not like drugs or like paper. They're made out of metal. They stick around for years," said Frank Occhipinti, the resident agent in charge of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

"We'll find that a particular firearm when we do trace it was purchased by some guy out of North Carolina in 1991 and there hasn't been activity with that firearm and now we see it in 2015. That firearm could have passed six, seven, eight owners before we got it."

Officers say it’s simple for a person who's not legally allowed to own a gun to get their hands on one in minutes. Cincinnati Police Officer Dan Kowalski and his colleagues on the ATF task force know the most common ways guns used in crimes are obtained. But to target the gun sellers, the officers must often work backwards to find them.

Federal and local law enforcement officials in Cincinnati are fighting a hard battle -- to quell a continuing stream of gun violence, with shootings now at a nine-year high. Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell, along with elected community leaders, announced a 90-day plan earlier this month to combat the gun violence.

RELATED: Federal officials will collect evidence from even Cincinnati shooting to link gun crimes

Officials say 213 people in Cincinnati have been shot this year and 29 have been killed by gunfire, as of 11:20 a.m on June 24. That includes back-to-back shootings early this week within one mile in Over-the-Rhine. One of those shootings left an 18-year-old man dead on Monday. The total also includes a Madisonville gun battle Friday that led to the death of Officer Sonny Kim and the suspected shooter, Trepierre Hummons.

“I don’t care what neighborhood you go to, it’s not just happening in the West End or Winton Terrace. It’s happening everywhere,” Kowalski said. “ You can go out to Fairfield, and there’s shootings out there. You can go out to Forrest Park and it’s happening out there. It’s not just an inner-city problem. It’s a regional problem. It’s a national problem if you really want to get into it."

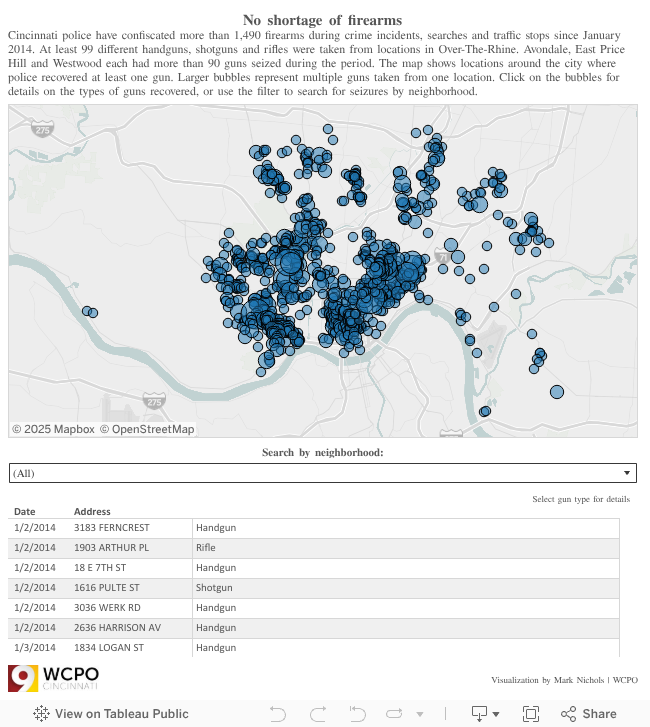

Cincinnati police confiscated more than 1,490 firearms during warrant searches of homes, traffic stops and incident investigations from January 1, 2014 thru May 30, 2015, according to a WCPO analysis of Cincinnati Police Department records. About 85 percent of the weapons seized were handguns — the easiest weapons to hide at a location or on a person or stash in a public place.

“If you see a group of guys in the ghetto or standing on a corner selling drugs…I will venture to say that people will not have guns on them. They'll be laying on a car tire or on a window sill or something where they will have access to them. Nobody wants to get caught with a gun but the gun will be in the area,” Kowalski said.

“If the police come up, all they have to do is walk away and hope the police don’t find that gun."

Most of the firearms confiscated by police during that 18-month period were taken from homes and buildings, WCPO’s analysis found. Others were taken from vehicles, found on a person without a carry permit during a search or found ditched in a public place.

MAP: Here's Where Cincinnati Police Confiscated The Most Guns

Federal ATF agents in Cincinnati seize weapons, too. But Occhipinti is not allowed to share how many.

The agency's National Tracing Center is the only organization authorized to trace U.S. and foreign manufactured firearms for federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. The federal Tihart Amendment limits the information ATF officials can share with the cities, states and members of the public about the weapons they trace.

How Criminals Get Their Guns

All it takes is money or drugs for someone who’s not allowed to own a gun to get their hands on one, members of the Cincinnati ATF task force say.

“It’s almost like a drug deal. If you’ve ever witnessed a drug deal or whatever, somebody comes up and says ‘Hey, I got a gun to sell. Will you give me heroin or money for it? They walk up and say, ‘Hey, here’s $200’ and you give me the gun,” said Kowalski.

Kowalski said many want to buy illegal guns on the street because they know the people they interact with also have guns, and they don’t want to be caught off-guard.

“There’s unfortunately a lot of money to be made in the drug trade, and they’ve got to protect what they believe is there,” he said.

A significant number of illegal guns on the street — especially ones that are trafficked — are bought in a straw purchase, Occhipinti and Kowalski said. That’s when a person who’s not allowed to buy a weapon pays someone who is to buy the gun from a licensed firearms dealer on their behalf. That person must lie on the federal form that prohibits a person from buying a gun for someone else.

Kowalski said people choose that illegal route because they want to ensure they get a nice gun.

“You don’t know what kind of gun you are getting off the street. If some heroin head comes up and says ‘Hey, I just broke into a house and I got the gun,’ you don’t know if that gun works,” he said.

Occhipinti said his agents see fewer guns that are stolen than the public would think.

“A very small percentage of the firearms we seize are reported stolen. Very small. A stolen gun on the street is considered a hot gun. If a criminal or a person knows that the firearm was a stolen gun, I think they’re less inclined to commit crimes with it just because it’s a stolen gun,” he said.

"They're passing them back and forth....Some of these guns have been around through years. It’ll hop around from person to person."

Some guns are purchased through the “gun show loophole,” officials say. That’s a term used to describe a kind of sale that doesn’t require a private gun seller to perform a background check on the buyer or keep a record of the sale. That type of transaction is legal in most states, including Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.

Tracing Guns An 'Archaic' Process

There’s no fast and easy way for ATF officials to trace a gun used in a crime — especially when the original owner bought it months or years before the crime occurred.

Once a request is sent to the National Tracing Center, officials at that center must contact the gun manufacturer with the serial number of the weapon seized to find out which store sold the gun.

Occhipinti said people who work at the tracing center then call the store and ask for the name of the person who completed the federal paperwork required to purchase it.

A tracing report is then provided to the local ATF field office who requested it. It includes the name of the original purchaser, the store who sold it, the name of the person who had the gun when it was seized and the number of days passed from the time the gun was purchased to the time a crime occurred.

“A huge misconception of the public is that we have a database where we can punch in the serial number of the firearm and we’ll know who bought it or that we would know how many guns the individual purchased. It’s very old school — a very slow process,” said Occhipinti. “It’s very archaic.”

It’s up to ATF agents and officers working alongside them to interview the original gun owner and find out who it was sold to along the way.

"You have to work backwards,” Kowalski said. “You’ll get a gun and it’ll be like ‘Man, this is too nice of a gun to be out on the streets. This is somebody’s gun.’"

They follow the trail of breadcrumbs, hoping it will eventually lead them to the source.

“A lot of these guys that commit straw purchasing are unaware of the impact the firearm can have if it’s in the wrong hands. Once they’re made aware of the impact of their crime…about 99 percent of the time, they’ll make a confession,” Occhipinti said.