CINCINNATI -- The glass doors of the Beer Cave are washed twice daily at Clough Pike Shell, a gas station convenience store in Union Township.

The tile floors are steam cleaned once a quarter.

“It’s definitely not a dirty store,” said Jason Wittekind, chief financial officer for the Clermont County store’s owner, Triumph Energy. “We really pride ourselves on taking the time and training the employees and doing the maintenance so that everything looks the way it should.“

Jason Wittekind

Family-owned Triumph Energy operates 22 gas stations under various brands. Wittekind said none of those stores ever ran afoul of health inspectors – until last year, when Clermont County Public Health found 81 violations at Clough Pike Shell.

RELATED: We tried the restaurant with the most violations

Wittekind thinks the store was the victim of an overzealous inspector who wrote 73 violations based on three visits last November.

Clermont County Environmental Health Director Maalinii Vijayan said the inspector “enforced the sections of the Ohio Uniform Food Safety Code appropriately,” adding that 42 citations came from follow-up inspections in which prior violations had not been corrected.

"They kept showing up in re-inspection reports until they got corrected,” Vijayan said. But they were “basically the same violations.”

After that experience, Wittekind wasn’t surprised to learn that Clermont County ranked fifth in the state last year in the number of violations per facility, based on WCPO’s analysis of 182,000 food-safety violations at 27,000 locations in Ohio.

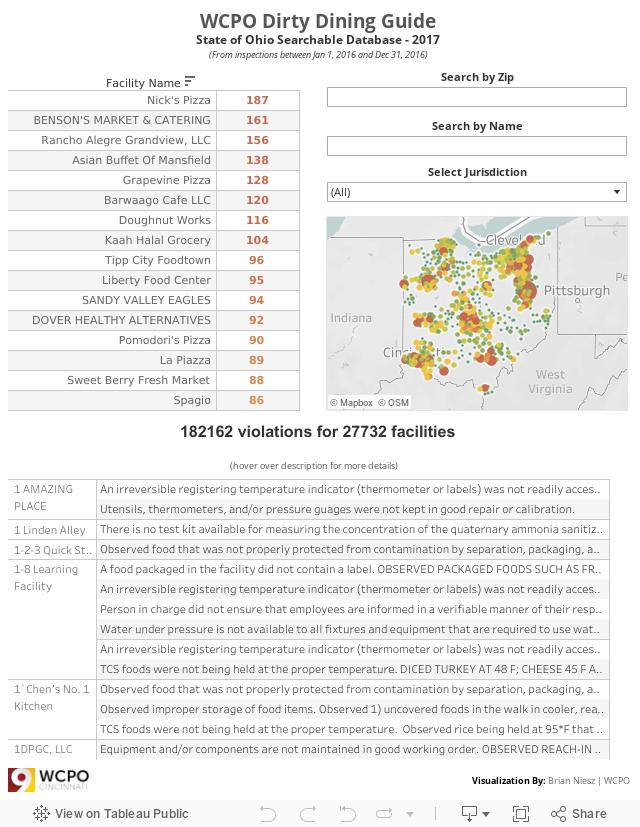

This is the fourth year WCPO has collected food-safety violations from multiple jurisdictions and then combined them into one searchable database.

But it's the first time WCPO obtained data from all over Ohio, in an attempt to show how health departments in Cleveland, Columbus, Toledo and elsewhere compare to local food-safety programs.

The analysis shows a wide variation in how inspectors enforce Ohio food safety rules, making it harder for companies to operate in multiple jurisdictions and raising the question of whether diners are more prone to certain problems in Cleveland than they would be in Cincinnati.

For example, Northeast Ohio inspectors are more likely to find fault with food-handling and hand-washing standards at food-service facilities, including restaurants, retail stores and sports venues. Hamilton County leads the state in problems citing the Ohio Revised Code section that has the header: “Controlling Pests.”

The WCPO analysis also shows that three of Cincinnati’s most popular sports venues rank in the top five statewide in the number of health-code violations received in 2016.

Another thing is clear from our analysis of data from 58 health department jurisdictions in Ohio: The Clough Pike Shell had some unusual violations last year.

For example, it had one of only 19 violations statewide involving Lunchables, the pre-packaged lunch kits that are supposed to be refrigerated at temperatures ranging from 32 to 40 degrees.

“TCS food items (cheese and Lunchables) were measured between 44-45°F in the Grab ‘N Go Refrigerated Merchandiser, “ said the public record on Sept. 28. “Items were placed on top of the air curtain instead of behind the air curtain.”

In addition, Clough Pike Shell received nine violations in November for ice build up in coolers. It’s extremely rare in Ohio, cited in less than 2 tenths of one percent of all inspections for the entire year.

‘We try to be as consistent as possible’

The differences from agency to agency illustrate just how much variation exists when it comes to the way different jurisdictions -- and even different inspectors -- inspect a food service operation, said O. Peter Snyder, president of SnyderHACCP, a food safety consulting firm near St. Paul, Minnesota. His opinions are based on more than 40 years in the industry.

"The basic code violations, the temperatures and times and things like that, they're pretty constant," Snyder said. "But then you get to the hand-wash station, and they come up with different ideas of what is effective hand washing and how do you measure cooking temperature."

Most general managers and business owners learn to put up with the variation and do what they must to make inspectors happy, he said.

The kitchen at Mt. Lookout Tavern was tidy during a recent visit.

"The industry basically says, if I say 'yes sir' or ‘no sir,' and I'm polite to the inspector, then they do their hour inspection and they go away for a year," Snyder said. "You don't want to argue with them."

The Ohio Revised Code requires local health departments to apply the state's food code uniformly across the state, and the Ohio Department of Health works to ensure that local agencies are consistent, said Jamie Higley, program administrator for the department's food safety program.

"It's good for food safety, and it's good for the food industry and the public that the food code be uniformly applied," Higley said. "We're all human. We all make mistakes, and we all see things differently. But we try to be as consistent as possible."

Restaurants respond to regulators

WCPO’s annual look at restaurant violations has expanded in each of the four years it has been presented, focusing on different themes every year – including how many violations are found in public places such as shopping malls and hospitals and whether certain kinds of ethnic restaurants and cuisine offerings draw more citations than others.

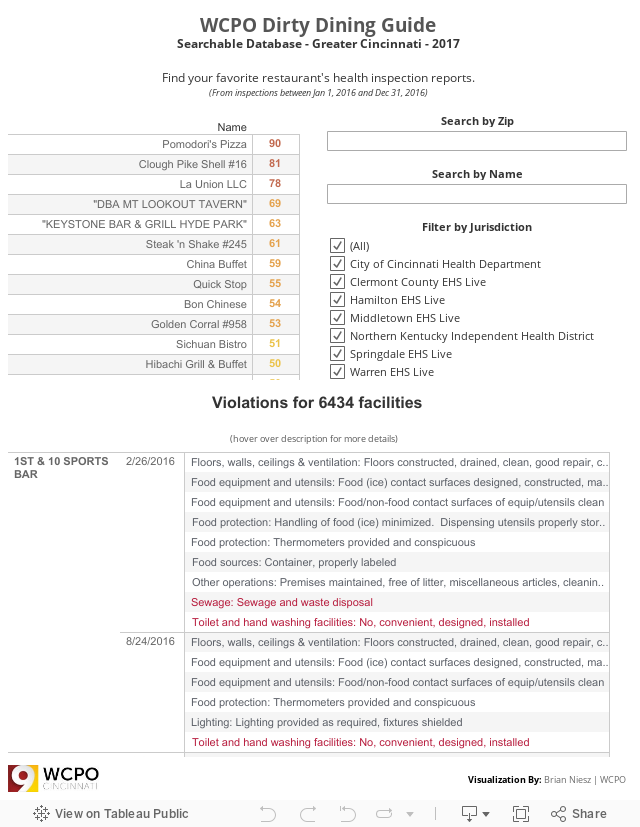

This year, WCPO revisits a theme from 2015, with analysis on whether certain jurisdictions are more aggressive than others. As in past years, WCPO obtained data directly from the city of Cincinnati and the Northern Kentucky Independent Health District, which regulates restaurants in Boone, Campbell, Kenton and Grant counties.

The Ohio Department of Health supplied data for Hamilton, Warren and Clermont counties, along with 54 other jurisdictions statewide. That includes the cities of Springdale and Middletown, featured for the first time in Dirty Dining.

The regional database has more than 45,000 violations at 6,434 locations, including Pomodori’s Pizza in Montgomery, which ranked first in the region and 13th in the state with 90 violations.

The statewide database includes food-safety violations at more than 27,000 locations statewide, including Nick's Pizza in Barberton, which ranked at the top of the list with 187 infractions. The owner could not reached but a person who answered the phone at Nick's said the restaurant moved to a new location in Novermber.

Hamilton County’s Health Department has placed Pomodori’s on probation as it works to recover from repeat violations for mice droppings and fruit flies found in the Remington Road restaurant.

Owner Tim McLane said he’s frustrated by the citations from 24 inspections since last February. But there is hope for Pomodori’s, which has only three violations since March 30 and no violations in its most recent inspection on April 28.

Mount Lookout Tavern made the list of top 10 violators, too. General Manager Greg Bailey chalked up the violations to a lot of "really minor stuff," 90 percent of which was corrected on the spot.

"I think we just needed to push onto the guys back there to make sure that we're keeping up the standards," he said. "Right now, everybody's really good at keeping it clean back there."

Personnel can have a big impact on how restaurants are rated, said Dan Cronican, managing partner of 4 Entertainment Group LLC. The company replaced the chef and sous chef at its Keystone Bar & Grill location in Hyde Park after a series of disappointing inspection results last year, Cronican said.

"We take food product safety very seriously," he said. "We are obviously disappointed and frustrated and even to the point of being embarrassed by the scores we received in Hyde Park. The people who were being paid to be the leaders for the kitchen -- they weren't living up to expectations."

Northern Kentucky’s highest-ranking restaurant had 45 violations and ranked 21st in the region, but that’s not necessarily an indication that kitchens are cleaner in the Bluegrass state. That’s because Northern Kentucky operates on a scoring system that triggers temporary closure for any restaurant that doesn’t get at least 60 points. Each restaurant starts every inspection with a perfect score of 100. Points are deducted based on the number and severity of violations. Eleven restaurants were suspended in 2016, most of them re-opening within a few days after a follow-up inspection brought higher scores.

But the Kentucky system shows how health departments vary in their approach to food-safety regulation. All state codes are based on federal standards, but the actual enforcement and the way violations are communicated to the public can vary by state, region, city and county.

In Kentucky, for example, a citation for violating a single code section can be documented with several observations in which inspectors describe multiple problems. In Ohio, those observations are more likely to be reported as additional violations. Not so in Kentucky.

At UC Health Stadium in Florence, for example, “Violation Code 23” was cited in the Aug. 31 inspection at the home of the Florence Freedom baseball team.Online visitors see the violation defined on the Health Department’s website as a plumbing problem.

But inspectors documented the following in the actual inspection document, not visible online:

“Ice bin and beer tap drains draining into buckets at Freedom Bar area; Hot water temperature at 80 degrees F at RF outfield bar area hand sink (needs to be at 100 degrees F); Leak present at upstairs VIP bar area hand sink.”

That’s three problems in three separate areas of the ballpark, but it only counted for one non-critical violation, a deduction of one point from its overall score. That inspection resulted in 14 other violations and a total score of 70 for the stadium. It corrected five of the problems before inspectors left the facility, and the stadium got a score of 86 in a follow-up inspection the same day.

Florence Freedom General Manager Josh Anderson said last year's low score was an anomaly for the ballpark, which had always gotten food inspection scores in the 90s before then.

"A lot of the things were very easily fixable," he said. "We were basically on cruise control with our inspections until the end of last year. That kind of gets your attention. And I've involved myself a lot more."

'Least of your worries'

Back at Clough Pike Shell, they’re celebrating a 2016 award from the Shell oil company, based on a variety of store-performance indicators, including cleanliness. The store ranked 36th out of 6,000 Shell stations nationwide in “secret shopper” reviews that took place in the second quarter of 2016. Wittekind was notified of the honor in October, one month before Clermont County found 73 problems in the facility.

Wittekind takes it all in stride. It’s customer satisfaction that matters most to him, not the praise and pans from outside reviewers.

“We always say inspection day is the least of your worries,” Wittekind said. “It’s the 30 days leading up to it, making sure you have consistent product in a safe environment. Customer satisfaction is our number one priority. So, if we have issues, we want to make sure they’re addressed even before the health inspector comes here.”