CINCINNATI - How much valuable advice could you deliver for $653 an hour? That’s what Cincinnati’s publicly traded companies paid the average corporate board member in 2016.

The value of their collective guidance is more difficult to discern.

“I think there’s plenty of room for improvement,” said Tim Meyer, president and chief investment officer at Meyer Capital Management in Anderson Township.

Macy’s Inc. and Kroger Co., for example, have lost a combined $14 billion in market value since the start of this year, as investors flee traditional retail stocks in the age of Amazon. Both companies generated billions in wealth for shareholders in the decade before the dive.

Should their boards be praised for helping managers develop winning strategies in the early 2000s or criticized for underestimating threats posed by discount rivals and online retailers?

“The jury is out for both Kroger and Macy’s on whether they have the expertise that’s required to fend off not only the Amazons of the world but just the whole sea change in consumer buying behavior,” Meyer said.

Corporate governance expert Charles Elson said shareholders usually don’t blame boards for strategic errors.

“The management runs companies,” said Elson, a finance professor at the University of Delaware. “The board’s role is to make sure management is running it appropriately. Unless you leave in place a bad manager, it’s hard to really blame a board.”

Macy’s and Kroger declined to make board members available for comment. Both issued statements defending the experience and value their boards provide.

“There are continuing challenges in our sector and changes in consumer shopping habits,” said Macy’s spokeswoman Andrea Schwartz. “Although we anticipate these changes to continue, our board and management is not standing still and is positioned to lead in this change.”

Kroger’s board has “a solid mix of tenure and innovative perspective” that helps managers create long-term value for shareholders, said Kroger spokeswoman Kristal Howard.

“Business backgrounds represented on the board include retail, finance, real estate, consumer packaged goods and manufacturing – all of which enable the board to actively participate in shaping Kroger’s strategy, including risk analysis and management,” she said.

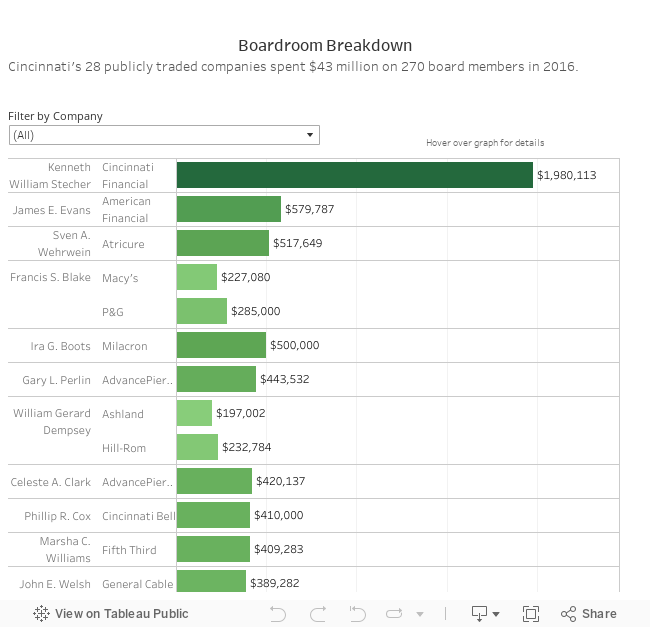

Boardroom breakdown

WCPO offers some insight into the life of a corporate director with a searchable database that shows what board members make and how much stock they own. The average compensation for 270 local directors is $160,000. The National Association of Corporate Directors says board members devote an average of 245 hours a year to meetings and preparation. So, the average local board member makes $653 an hour.

S&P Capital IQ pulled the information from annual reports to shareholders. It also supplied three-year estimates on total shareholder return, which is the value of stock price changes plus dividends. WCPO found little correlation board pay and shareholder return. But there is a correlation between pay and company size, as measured by the total value of all stock held by shareholders.

When it comes to director pay, Elson said he looks for companies that pay a mix of cash and stock-based pay. That gives directors an ownership stake in the companies they serve, so their interests are aligned with shareholders.

There are 20 local companies that spent more than $1 million on their boards in 2016, but Meyer and Elson agreed that most shareholders wouldn’t see a problem with that.

“If the company is chronically under-performing, I don’t know that pressuring the company to go out and get bargain basement talent for the board is going to address your problems,” Meyer said. “If anything, if you’re a Macy’s or Kroger looking at fending off Amazon, I’d be out paying up for whatever kind of talent I felt I had to get in order to defend the business.”

But Meyer isn’t sure about the board talent at one of Cincinnati’s biggest companies, his former employer, Procter & Gamble Co.

“Sometimes I look at the people on the board and I wonder how they got there,” he said. “P&G has the former president of Mexico on their board. I wonder what he brings to the party.”

Meyer is a former business analyst at P&G who is “very skeptical” that P&G’s shrink-to-grow business strategy – announced by former CEO A.G. Lafley in July, 2014 – is actually working.

The plan called for the sale of about 100 brands so the company could focus on those with the best growth prospects. The targeted brands are all gone but in P&G’s most recent quarter net sales declined in four of P&G’s five major business segments. P&G blamed foreign-exchange fluctuations for much of the sluggish growth and pointed to positive trends in China and continued sales growth for core products, such as Tide Pods, Gain Flings and Oral-B toothpaste.

“It’s certainly a board problem,” said Meyer, because P&G has gone years without a solution. Meyer thinks activist investor Trian Partners will push for “material changes to the board” this year, a move that could eventually lead to a breakup of the company.

“The fundamental business, especially the top line (revenue), has not delivered for a long time, several years at least,” Meyer said. “From an innovation standpoint, which was always what P&G was known for, the new-product breakthroughs are few and far between.”

Trian Partners declined to comment, but a published report said the company – which in February announced a $3.5 billion stake in P&G – has filed notice to seek a board seat at the company’s annual meeting in October. P&G spokesman Damon Jones wouldn’t confirm that, but said the company welcomes input from shareholders.

“We're confident in the plan we have to return to growth and we are encouraged by the progress we continue to make,” Jones said.

If P&G shareholders are asked to shake up the board, their decisions are likely to be based on how the board responded over time. David Taylor is the company’s third CEO since 2012. Its restructuring and divestiture initiatives have literally re-shaped the company. Whether they missed the mark on strategy could ultimately be less important to shareholders than why they missed the mark, Elson said.

“Did they miss it because they were too captivated by management and didn’t ask the right questions? Or did they miss it because everyone missed it? Sometimes, luck is viewed as brilliance and brilliance is unlucky,” he said.